|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

Copies of some of Kōrinís flower-bird pictures were included in woodblock-printed art instruction books published intermittently after his death in 1716 (Table 3.7). In a few other books twentieth century artists used the Rinpa style to produce new flower-bird designs.

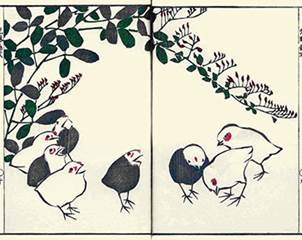

Four pictures from these books are shown in Figure 3.16 to illustrate the Rinpa style. Flower-bird subjects were typically drawn in simplified form using curved lines. The use of curved, instead of straight, lines and simplified, instead of detailed, form helped to create the illusion that the viewer was seeing an active, rather than passive, subject. To strengthen this illusion multiple, instead of single, objects (i.e., flowers or birds) were included which gave the picture a sense of rhythm or motion. When flowers or birds were arranged in groups it implied that they were interactive.

Figure 3.16. Four examples of flower-bird pictures drawn in the Rinpa style.

The use of color in these pictures ranged from none to partial or full color. Colors chosen for flowers and birds were not always accurate suggesting that visual appeal was sometimes a more important consideration. Pictures almost always featured a flower or bird that had symbolic association with a particular season of the year or with a human feeling in ancient court culture (i.e., 97% of pictures included in this analysis).

3.6.3†† Summary and Comparison A new style of art was created by Rinpa artists for members of the Japanese imperial court, the aristocracy and rich merchants who preferred themes and seasonal imagery associated with Japanese court culture to Chinese-themed art produced by Kanō artists for the military elite and to Ukiyo-e art produced for less wealthy merchants and other townsmen. The name Rinpa refers to Kōrin (rin) Ogata who was a prominent member of this school (pa) in the late seventeenth century and early eighteenth century. One distinctive feature of Rinpa art is the artistís use of curved lines to drawn subjects with simplified shapes. Consequently, flowers and birds drawn by Rinpa (R) artists are even less accurate than those drawn by either Kanō-influenced (K) or Ukiyo-e (U) artists (i.e., flower and bird shape accurate for 30% R versus 46% K versus 53% U of pictures included in this analysis). A second important feature of Rinpa pictures is the repetition of objects (i.e., flowers or birds) which helps to create an illusion of motion and life. Of the pictures included in this analysis, 62% had multiple flowers or birds compared to 43% for Kanō-influenced pictures and 39% for Ukiyo-e pictures. Like Kanō-influenced and Ukiyo-e artists, Rinpa artists tried to reveal the inner spirit of their subjects by showing birds in an active position (77% R versus 70% K versus 75% U) or arranged diagonally with flowers (74% R versus 66% K versus 79% U). However, unlike Kanō-influenced and Ukiyo-e artists, Rinpa artists rarely showed birds with rough body-edges (i.e., 8% R versus 33% K versus 55% U). The use of color in woodblock-printed pictures of Rinpa art ranged from none to full color. The color scheme used for flower-bird pictures included in this analysis was accurate only 24% of the time, compared to 56% for Ukiyo-e pictures and 6% for Kanō-influenced pictures. Initial limitations to woodblock printing technology explains the sparing use of color before the 1760s but it is surprising that books published later did not show the bold, rich color that was a feature of many of Kōrinís paintings. All Rinpa-style flower-bird pictures were published in art instruction books after Kōrinís death. The number of such books is smaller than the number featuring flower-birds drawn in Kanō-influenced or Ukiyo-e styles (i.e., 12 R books versus 20 K versus 51 U for books included in this analysis). This difference likely reflects the smaller size of the audience for Rinpa art than for Kanō-influenced and Ukiyo-e art.

3.7 Style 4 - Nagasaki School †長崎派 In the 1630s Tokugawa government leaders implemented a new foreign policy to help them maintain order by reducing potentially disruptive foreign influences. This policy forbade Japanese citizens to travel abroad, restricted foreign visitors and trade to the port city of Nagasaki and banned foreign books. The ban on foreign books was lifted in 1720 but travel restrictions remained in effect until the 1850s. The only foreign visitors allowed into Nagasaki between the 1630s and 1850s were the Chinese, Koreans, and Dutch. Foreign visitors and imported books introduced a number of new art styles to Japan. One new Chinese style was called Nagasaki to reflect its point of origin in Japan.

For Japanese artists, initial information about the Nagasaki style came from two Chinese painting manuals, listed below, and a Chinese visitor, Shen Nanpin (沈 南蘋). He was a Qing Dynasty flower-bird painter who visited Japan between 1731 and 1733 (Hickman and Satō, 1989). Zhengyan Hu (胡 正言). 1643. Ten Bamboo Studio Manual of Painting (Jitchikusai Shogafu 十竹斎書画譜) Gai Wang (王 概). 1679, 1701. The Mustard Seed Garden Manual of Painting (Kaishien Gaden 芥子園画伝) Ten bamboo studio is the name of the house where the author and his friends gathered to practice their late Ming Dynasty-style painting. Mustard seed garden refers to the Nanking villa of Li Yu (李 漁) who collaborated on the production of this painting manual about early Qing Dynasty-style painting. Both manuals gave instructions for painting a variety of subjects, including flowers and birds. In the late eighteenth century and early nineteenth century Japanese artists who were attracted to the Nagasaki style published additional art instruction books which also included flower-bird pictures (Table 3.8). Of these artists, Shiseki Sō was the most active proponent of the Nagasaki style.

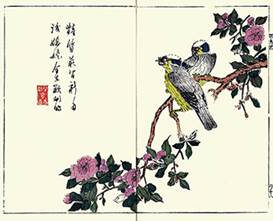

To illustrate Nagasaki style, a flower-bird picture from each of the two Chinese woodblock-printed painting manuals is given in Figure 3.17. Also included in Figure 3.17 are four examples of flower-bird pictures drawn by Japanese artists in the Nagasaki style. A novel feature of this style, evident in each of these pictures, is the virtual elimination of the black outline used by previous styles to define the shape of an object. Instead, shape was defined by applying an area - not line - of pigment, either black or combination of some other colors. The same color was used for an objectís edges and its interior. In previous styles an objectís edges were black while its interior was some other color. Eliminating the black outline made an object look more realistic. The word boneless is often used to describe a style where objects are not outlined in black because objects lack the skeleton (i.e., bones) created with a black outline (Briessen, 1962). Another novel feature of pictures in the Chinese painting manuals was the extensive use of color for flowers and birds. When these manuals were first introduced to Japan multi-colored woodblock prints were a novelty. Not until the 1760s was full color printing possible in Japan. In the first Nagasaki-style art book published by a Japanese artist all pictures were black-and-white (Figure 3.17c). Later books included a mixture of black-and-white and color pictures (Figure 3.17d,e). Later still the use of full color became the norm (Figure 3.17f). The addition of color made flowers and birds look more realistic but the colors chosen by both Chinese and Japanese artists were not always true to life. Nor were the shapes of flowers and birds always drawn accurately. Typical of Chinese-style painting, the artistís primary objective was not to reveal a subjectís external appearance but rather its inner spirit. To achieve this objective birds were often shown in an active pose (Figure 3.17 a,c,d,e) or arranged diagonally with flowers (Figure 3.17b,d,f). Many birds also had rough body-edges (Figure 3.17b,d,e,f).

Figure 3.17. Six examples of flower-bird pictures drawn in the Nagasaki style.

3.7.3†† Summary and Comparison Artists who were seeking an alternative to the government-sponsored Kanō style of Chinese painting looked to foreign art books and artists entering Japan through the port city of Nagasaki. Between the 1630s and 1850s Nagasaki was the only city where government officials allowed the entry of foreign influences into Japan. One of the alternative styles of Chinese painting found in Nagasaki was called the Nagasaki style. For flower-bird pictures, the Nagasaki style differs from Kanō-style Chinese painting in some respects but is similar in others. The most important difference is that objects are Ďbonelessí in Nagasaki-style pictures versus Ďbonedí in Kanō-style pictures. Kanō-influenced artists used a black line to define the shape of an object, similar to creating a skeleton of bones. Nagasaki-style artists largely eliminated this black outline. An area - not line - of pigment was applied to define an objectís shape. Initially, both Kanō-style and Nagasaki-style flower-bird pictures were black-and-white but later Nagasaki-style pictures featured more color than Kanō-style pictures. However, the colors were not always true to life so there was relatively little difference in the accuracy of the color schemes of Nagasaki (N) and Kanō (K) -style pictures (i.e., color accurate for 16% N versus 6% K of pictures included in this analysis). The shapes of flowers and birds were drawn accurately only about half the time (i.e., shape accurate for 51% N versus 46% K of pictures included in this analysis). In an attempt to reveal the inner spirit of their subjects, both Nagasaki-style and Kanō-influenced artists often showed birds in an active position (72% N versus 70% K) and arranged diagonally with flowers (74% N versus 66% K). Rough bird body-edges were more evident in Nagasaki-style pictures (63% N versus 33% K). Flowers and birds that were symbolically associated with human feelings or with a season of the year were the favorite subjects of both Nagasaki-style and Kanō-influenced artists (i.e., symbolic association evident in 92% N and 92% K of pictures included in this analysis). Woodblock-printed flower-bird pictures drawn by Japanese artists in the Nagasaki style are only found in a modest number of art instruction books published between the 1760s and 1890s. Most Kanō-influenced flower-bird pictures are also found in art instruction books published earlier, starting in the 1720s.

3.8 Style 5 - Nanga School †南画派 When Tokugawa military leaders took power in the early 1600s they promoted Chinese culture and art. Artists of the Kanō family were commissioned to produce artwork similar in style to that produced for the Chinese imperial court by Chinese professional painters. This style was called Northern School Painting (Hokushūga北宗画) by the Chinese art critic Qichang Dong (其昌 董) (Parent, 2001). He coined the term Southern School Painting (Nanshūga 南宗画) to describe another painting style practiced by Chinese amateurs who painted for self-expression and creativity. Many of these amateurs were scholars and bureaucrats in the Chinese government. Qichang chose the words Northern and Southern because differences between the two painting styles paralleled differences in beliefs of Northern and Southern sects of Zen Buddhism. The Northern sect believed that enlightenment was best achieved through continued practice while the Southern sect believed that enlightenment came spontaneously. Southern School Painting was more spontaneous, less practiced than Northern School Painting. In the eighteenth century, Southern School Painting was introduced to the Japanese by Chinese Buddhist monks and other Chinese visitors to the port city of Nagasaki (Yonezawa and Yoshizawa, 1974). Art books and paintings imported from China through Nagasaki provided the Japanese with additional examples of Southern School Painting. To describe this new style of Chinese painting the Japanese shortened the word Nanshūga to Nanga which means Southern (nan) Painting (ga). The word Bunjinga (文人画) was also used to describe this new style. Bunjinga means literary person (bunjin) painting (ga) which refers to its Chinese scholar practitioners. In Japan this style was adopted not just by scholars but also by people from other social classes and occupations (Addiss, 2002). Consequently, the word Bunjinga is used less often than the word Nanga with reference to this painting style. The broad appeal of Nanga may reflect the fact that it required little technical artistic skill and, more importantly, it permitted personal expression. To provide students of the Nanga style with sample pictures and instruction, Japanese artists published a number of woodblock-printed books in the nineteenth century. Other Nanga-style woodblock prints were sold individually for decorative purposes. Each of these two uses is described in more detail below.

Woodblock-printed books that were published to illustrate the Nanga style could include pictures of flowers and birds, landscapes, and human activity. Books with flower-bird pictures are listed in Table 3.9. These books either included works by a number of different artists or, more commonly, by a single artist. Bunchō Tani was a prominent, early contributor to Nanga art as was Katei Taki later.

Table 3.9. Publication date and author of books with Nanga-style flower-bird pictures drawn by a single artist (blank) or by more than one artist (*). Book titles are included in Chapter 4 under the authorsí names.

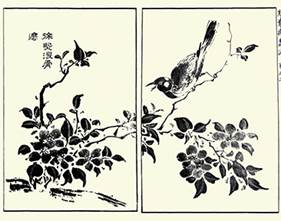

Four pictures from these books are given in Figure 3.18 to show important features of the Nanga style. Nanga artists used a combination of short lines and areas of pigment to create the shapes of flowers and birds. These shapes were typically distorted (Figure 3.18a,b,c,d) and often incomplete (Figure 3.18a,b). Color was used sparingly and normally too few colors were included to be able to depict flowers and birds accurately. In addition, pigment was applied unevenly creating a blotchy color scheme that was not true to life. All of these inaccuracies make pictures look extremely amateurish. However, the aim of Nanga artists was not to draw a professional-looking picture that mimicked reality but instead to express their personal feelings about the subject matter in a highly creative way (Stanley-Baker, 1992). Their spontaneous thoughts about the subjects were transferred to paper to reveal the subjectsí spirit rather than their external form. A sense of movement was introduced by using incomplete shapes for the subjects. In addition, birds were often shown in an active pose (Figure 3.18a,c) or arranged diagonally with flowers (Figure 3.18b,d). Rough bird body-edges were also typical (Figure 3.18a,c,d). Figure 3.18. Four examples of flower-bird pictures drawn in the Nanga style.

Some Nanga-style, woodblock-printed pictures of flowers and birds were intended to be used for decoration instead of art instruction. These pictures were sold individually instead of as a group in a book. Two examples are included in Figure 3.19. The first example is octagonal in shape making it suitable for use as part of a hand-held fan. The second is rectangular in shape and more suited to wall decoration. Stylistic features of these decorative prints match those of prints in the art instruction books described above. Figure 3.19. Two examples of decorative prints drawn in the Nanga style.

3.8.4†† Summary and Comparison A new style of Chinese art, called Nanshūga in China, was introduced to Japan through the port city of Nagasaki in the eighteenth century. The name Nanshūga was abbreviated to Nanga (i.e., southern painting) by the Japanese. In China this style was favored by educated amateurs who sought an alternative to the Hokushūga style practiced by professional painters. In Japan, people from all social classes and occupations were attracted to the Nanga style as an alternative to the prevailing Kanō style which was the Japanese equivalent of Chinese Hokushūga. Nanga and Kanō styles differed in a number of ways. Kanō-style flowers and birds were Ďbonedí while Nanga-style flowers and birds were Ďbonelessí. Boned refers to the black line used by Kanō-influenced artists to outline completely the shape of a flower or bird. Nanga artists used a combination of short lines and areas of pigment to only suggest the shape of a flower or bird. Shape was often left incomplete for viewers to complete in their own minds. Nanga-stlye (N) shapes were typically more distorted than Kanō-style (K) shapes (i.e., shape accurate for 31% N versus 46% K of pictures included in this analysis). These differences reflect the Nanga artistís more spontaneous approach to his art. Creativity and personal expression were much more important to Nanga artists than to Kanō-influenced artists. The use of color also differed between Kanō-influenced and Nanga artists. Technical limitations to woodblock printing meant that most Kanō-influenced pictures were black-and-white. Full-color printing was available to Nanga artists and most used colors other than just black and white. However, the range of colors chosen was rarely adequate to show flowers and birds accurately. In addition, color was applied unevenly creating blotchy-looking objects. Only 12% of the Nanga-style pictures included in this analysis had accurate color schemes for flowers and birds. The creative use of color was more important than accuracy for the Nanga artist. Revealing a subjectís inner spirit was an important goal of both Kanō-influenced (K) and Nanga (N) artists. To help achieve this goal, birds were often shown in an active position (i.e., 71% N and 70% K of pictures included in this analysis) and arranged diagonally with flowers (i.e., 77% N and 66% K of pictures). Nanga artists made greater use of rough bird body-edges (i.e., 55% N versus 33% K of pictures) and incomplete shapes to imply rapid movement (i.e., 42% N versus 8% K of pictures). Some Nanga-style, woodblock-printed pictures of flowers and birds were sold individually for decorative purposes (e.g., fans, wall decoration) but the majority was published in art instruction books in the nineteenth century, similar to Kanō-style prints published earlier. |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

Chapter 3 Ė Styles 6-8 or Back to Guides

|

|